What you can fully deduct? What is partially deductible? What can’t you deduct at all?

A lot of confusion exists on the issue of how much of a given food/meal expense is deductible. And rightfully so because some food/meals are fully deductible, some are only 50% deductible and some aren’t deductible at all.

Congress and the IRS have been legislating and regulating this issue for decades. One has to remember that tax law does not necessarily have logic supporting it. Taxes are imposed in order to finance the operations of, and implement the policies of, the government. Having said that, the logic surrounding the deductibility of food/meals goes something like this:

You can fully deduct food /meals when the food or meal has an important business purpose, but the food/meal itself is not really intended to benefit the person who consumes the food as much as it benefits the business. When there is really no business purpose or benefit to the meal, it isn’t deductible at all. When the food/meal starts to provide a direct benefit to those consuming it, yet still has a valid business purpose, you are likely getting into the area of partial deductibility. Got it? I didn’t think so.

consumes the food as much as it benefits the business. When there is really no business purpose or benefit to the meal, it isn’t deductible at all. When the food/meal starts to provide a direct benefit to those consuming it, yet still has a valid business purpose, you are likely getting into the area of partial deductibility. Got it? I didn’t think so.

So let’s just break this down into the categories. Here is what is fully deductible:

- Meals for which the business is reimbursed. If you charge your customers for meals you consume, for example while on a job site, you can fully deduct those meals. In truth, the charge and reimbursement likely offset each other rendering the event tax neutral.

- Food/meal costs for the company holiday party or picnic are considered immaterial employee benefits and are fully deductible.

- Meals provided on your premises for more than half of your employees that is for the convenience of the employer are 100% deductible. This would be in cases where a business keeps staff late or on weekends for specific business purposes.

- Food/meals made available to the public, usually for promotional or advertising purposes.

- Snacks and beverages provided to employees.Snacks, not steaks.

Here is what is 50% deductible:

- Meals with clients, customers and vendors that will benefit the business. This would mean the typical business lunch or dinner.

- Meals while on business travel including seminars, conventions and the like get the 50% treatment.

- Meals paid for in conjunction with office, stockholders, directors and employee meetings are half deductible.

Here are a couple of examples of food/meals expenses I would consider NON-deductible:

- A meal you consume while working through your lunch hour is not deductible.

- If you were joined at an otherwise deductible business meal by someone un-associated with the business, and has no business purpose for attending, I wouldn’t deduct the cost of that person’s meal.

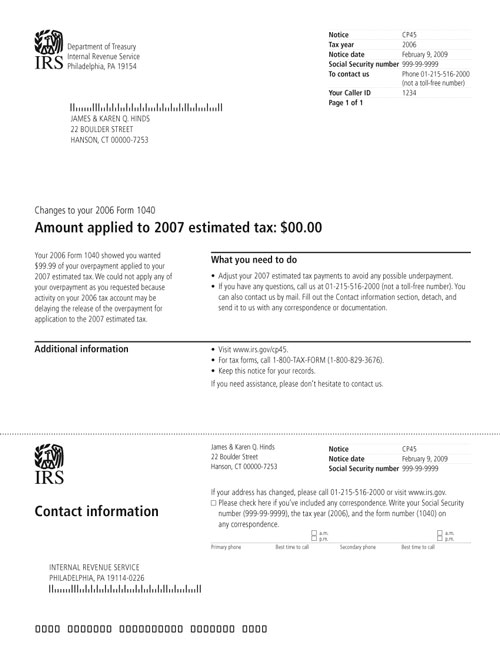

As always, there are grey areas, but I encourage clients when in doubt to clearly document the business purpose of any meal or food expenditure. In truth, the IRS will be hard-pressed to debate you on business purpose if it is clearly stated and sounds legit. This is because the IRS has much greater success denying deductibility because a taxpayer just kept the receipt or included a vague statement to support the business purpose of the meal. “Lunch with Bob Smith “doesn’t cut it and the IRS knows this. If you take the extra 30 seconds to write down that business purpose, you increase your chance of getting the deduction under audit. Omit that purpose and you will lose the deduction entirely.

Another tip: I encourage clients to keep 2 separate ledger accounts for meals and entertainment in their accounting records. One to record the 100% deductible expenditures and one for the 50% deductible items. This will save you tax dollars to be sure.

If you have questions on this, by all means drop me a line and we’ll talk about it.

making examples of them (yes the IRS specifically issues press releases when they get someone on tax fraud to scare the rest of us) the hope is that they get better compliance.

making examples of them (yes the IRS specifically issues press releases when they get someone on tax fraud to scare the rest of us) the hope is that they get better compliance.